Dr Inja Stanović

About

Biography

Dr Inja Stanović is a Croatian pianist and a published author. Inja is a Senior Researcher at the University of Surrey, where she directs the Early Recordings Association, ERA. Her recent publications include co-edited volume Early Sound Recordings: Academic Research and Practice (Routledge, 2023), and a free-source research album Austro-German Revivals: (Re)constructing Acoustic Recordings (University of Huddersfield Press, 2022).

Areas of specialism

My qualifications

Previous roles

ResearchResearch interests

Early sound recordings and mechanical recording technologies. The impact of early recording technologies on performance, and historic stylistic practices.

Sound heritage restored: Developing repair methods for wax cylinders

Sound heritage restored: Developing repair methods for wax cylinders; PI. Value £10,000.

Research projects

Redefining Early Recordings as Sources for Performance Practice and History was an AHRC-funded research network led by PI Dr Eva Moreda Rodríguez and CoI Dr Inja Stanović. It brought together researchers, performers, curators, technicians and collectors from all over the world who use early recordings (roughly defined as pre-Second World War) as sources for the study of music history and music performance.

The network ran from March 2021 to March 2023. On the project's website (https://earlyrecordingsconference.wordpress.com) we have a ‘Research resources’ section for researchers new to early recordings, and under ‘Past activities’ we have posted the programmes (and, in some cases, presentation recordings) of three early recording conferences we held in 2019, 2020 and 2021 prior to the set-up of the AHRC network.

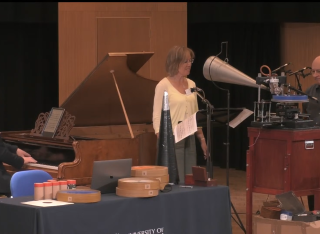

“(Re)constructing Early Recordings: a guide for historically-informed performance” was a Leverhulme-funded research project that investigated the production of early recordings (focussing on wax cylinders and discs). Through a (re)construction of mechanical recording methods, musical performances were captured, analysed, and made available to the international community of musical researchers. All recordings were simultaneously recorded using contemporary digital technologies, allowing for direct comparisons between the acoustic and digital recordings. Results, which integrated creative practice and theoretical research, illuminated both performance and recording practices of the past, and elaborated a method for future research into early recordings.

The field of the historically informed performance practice is continually blossoming, and in the last years there is a hight rise of interest in early recordings and using them as research evidence in context of performing styles of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, as everybody who ever recorded their playing will know – we modify our performance in order to record successfully. Every performance is context based, and we would not play in the same manner in a massive concert hall or a small church. I’ve started to be interested in the path which leads to the end sonic result many admire through early recordings. How do you need to play to record successfully, how does it feel to have the dynamic restrictions when you play, do you need to sit or hold your instrument differently, or – especially from the twenty first century perspective – how does it feel to record in a single take, and then not be able to hear the payback for days?

My research project was investigating exactly this – what do we as performers have to do, or negotiate in order to record mechanically. This project would not exist without generous help of Duncan Miller, acoustic engineer and also owner of all the equipment we are using, whose company produces all the wax blanks needed. The sessions were simultaneously recorded digitally by my husband, Dr. Adam Stanović from the London College of Communication (University of Arts), who also did a very important aftermath of comparing and analysing the digital recordings with the acoustic recording transfers.

Essentially practice-led, involving both performance and recording, the central research method in this project was autoethnography. Rather than fixating upon the product of the recording sessions, I focus on the process of performing and recording. By doing so, I was able to understand some of the various problems recording musicians faced around the end of the century, assess the many ways in which musicians might have navigated such recording processes, and identify ways in which such recordings might reveal and display aspects of musical practices that are otherwise beyond our reach.

Sound heritage restored: Developing repair methods for wax cylinders3M Buckley Innovation Centre

Research interests

Early sound recordings and mechanical recording technologies. The impact of early recording technologies on performance, and historic stylistic practices.

Sound heritage restored: Developing repair methods for wax cylinders

Sound heritage restored: Developing repair methods for wax cylinders; PI. Value £10,000.

Research projects

Redefining Early Recordings as Sources for Performance Practice and History was an AHRC-funded research network led by PI Dr Eva Moreda Rodríguez and CoI Dr Inja Stanović. It brought together researchers, performers, curators, technicians and collectors from all over the world who use early recordings (roughly defined as pre-Second World War) as sources for the study of music history and music performance.

The network ran from March 2021 to March 2023. On the project's website (https://earlyrecordingsconference.wordpress.com) we have a ‘Research resources’ section for researchers new to early recordings, and under ‘Past activities’ we have posted the programmes (and, in some cases, presentation recordings) of three early recording conferences we held in 2019, 2020 and 2021 prior to the set-up of the AHRC network.

“(Re)constructing Early Recordings: a guide for historically-informed performance” was a Leverhulme-funded research project that investigated the production of early recordings (focussing on wax cylinders and discs). Through a (re)construction of mechanical recording methods, musical performances were captured, analysed, and made available to the international community of musical researchers. All recordings were simultaneously recorded using contemporary digital technologies, allowing for direct comparisons between the acoustic and digital recordings. Results, which integrated creative practice and theoretical research, illuminated both performance and recording practices of the past, and elaborated a method for future research into early recordings.

The field of the historically informed performance practice is continually blossoming, and in the last years there is a hight rise of interest in early recordings and using them as research evidence in context of performing styles of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, as everybody who ever recorded their playing will know – we modify our performance in order to record successfully. Every performance is context based, and we would not play in the same manner in a massive concert hall or a small church. I’ve started to be interested in the path which leads to the end sonic result many admire through early recordings. How do you need to play to record successfully, how does it feel to have the dynamic restrictions when you play, do you need to sit or hold your instrument differently, or – especially from the twenty first century perspective – how does it feel to record in a single take, and then not be able to hear the payback for days?

My research project was investigating exactly this – what do we as performers have to do, or negotiate in order to record mechanically. This project would not exist without generous help of Duncan Miller, acoustic engineer and also owner of all the equipment we are using, whose company produces all the wax blanks needed. The sessions were simultaneously recorded digitally by my husband, Dr. Adam Stanović from the London College of Communication (University of Arts), who also did a very important aftermath of comparing and analysing the digital recordings with the acoustic recording transfers.

Essentially practice-led, involving both performance and recording, the central research method in this project was autoethnography. Rather than fixating upon the product of the recording sessions, I focus on the process of performing and recording. By doing so, I was able to understand some of the various problems recording musicians faced around the end of the century, assess the many ways in which musicians might have navigated such recording processes, and identify ways in which such recordings might reveal and display aspects of musical practices that are otherwise beyond our reach.

3M Buckley Innovation Centre

Publications

This article presents one of the experimental case studies conducted during Inja Stanovic's four-year research project (Re)constructing Early Recordings: A Guide for Historically-Informed Performance. In this project, various acoustic recordings were recreated in order to understand some of the musical, technical and historical contexts associated with early sound recordings. One of the case-studies was created with Jeroen Billiet, focusing on making the acoustic ten-inch disc for horn and piano. Through our observations about mechanical recording process, we hope to offer insights into romantic playing practices and historical recording techniques. We also supply digital transfers of our recordings of music for piano and horn.

The use of historical recordings as primary sources is relatively well established in both musicology and performance studies and has demonstrated how early recording technologies transformed the ways in which musicians and audiences engaged with music. This edited volume offers a timely snapshot of a wide range of contemporary research in the area of performance practice and performance histories, inviting readers to consider the wide range of research methods that are used in this ever-expanding area of scholarship. The volume brings together a diverse team of researchers who all use early recordings as their primary source to research performance in its broadest sense in a wide range of repertoires within and on the margins of the classical canon – from the analysis of specific performing practices and parameters in certain repertoires, to broader contextual issues that call attention to the relationship between recorded performance and topics such as analysis, notation and composition. Including a range of accessible music examples, which allow readers to experience the music under discussion, this book is designed to engage with academic and non-academic readers alike, being an ideal research aid for students, scholars and performers, as well as an interesting read for early sound recording enthusiasts.

Early sound recordings offer an invaluable insight into changing fashions of, and stylistic conventions in, performance practice that is rarely discernible from either written documents or musical scores. This chapter considers such insights, focussing upon Vladimir de Pachmann’s (1848-1933) piano roll and acoustic recordings of Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27 No. 2 (Welte piano roll, 1906; Colombia acoustic recording, 1916; HMV electrical recording, 1925). These three recordings offer a wealth of information relative to rhythmic alterations, tempo modifications, tempo rubato, asynchronous playing and unnotated arpeggiation. The chapter explores them using a range of sonic visualiser tools, in order to 1) clarify differences between various historical recording technologies; 2) point out historical recording variables that could be compared and analysed; and 3) further understand pianistic tools Pachmann used to build three interpretations at different stages of his life.

Book chapter in: Softwaregestützte Interpretationsforschung: Grundsätze, Desiderate und Grenzen (ed. Julian Caskel, Frithjof Vollmer, Thomas Wozonig (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, December 2022)

Great Britain occupies a unique position in Chopin’s reception history: while it was one of the three locations for the publication of his first editions, Great Britain produced highly polarised reactions to Chopin’s music, greatly influencing the reception and performances of his works after his death. Throughout the nineteenth century Chopin's music was published by a significant number of British publishers, besides Wessel; the Deux Valses Melancoliques were published by Ewer in 1854, Boosey published a new edition of mazurkas in 1860, and the twelve polonaises appeared with Augener in 1872, just to name a few. Throughout nineteenth-century Britain, the demand for drawing room pieces was high and Chopin's piano pieces were frequently published in amateur score collections; as early as 1836, Chopin's pieces were published in Wessel's L'Amateur Pianiste collections. This article considers the music of Chopin in the context of amateur piano playing in the nineteenth-century Britain, paying particular attention to the collections of his music; Chopin's compositions are discussed relative to the popularity of pieces within those collections and editorial changes to Chopin's writing. In doing so, the findings from this research present some of the numerous subtexts underlying the respective positions of amateur piano playing.

Book chapter in: The integration of a work: from miniature to large scale, Research and Publishing Department of The Fryderyk Chopin Institute

Historically-informed performance practice is inherently complex; not only are instruments and playing styles relative to specific cultural, social and historical contexts, literary sources are often subjective and, as with the performances that they describe, a product of their own time. Practice can also be informed by examination of early recordings, which serve to illuminate stylistic conventions of past eras. By studying such recordings, the principles of previous performances and interpretations can be systematically studied and understood. These recordings do not merely offer a window into the sound-world of past performances, however; they also offer a wealth of information about the physical nature of performance itself. As such, they may serve as a model, or exemplar, for contemporary performances of the same works. Despite this, contemporary performers should not merely copy and paste what they hear through such recordings; the interpretative choices made by recording musicians were likely to have been specific to both the recording medium and the instruments of the time; since many of the physical, haptic and proprioceptive cues employed by those musicians cannot be abstracted from, or identified through, listening alone, one must instead strive to understand the stylistic conventions in the context of the recording medium originally employed.

This lecture-recital focuses upon a range of late nineteenth-century pianistic expressive techniques, including various types of rubato, rhythmic alterations, dislocation between two hands, unnotated arpeggiation, and textual alterations, with particular reference to Frédéric Chopin’s Nocturnes. Due to their popularity, Chopin’s Nocturnes have a recording history dating back to the 1890s. As such, there are numerous recordings which can testify changes in performance styles in the intervening time. Importantly, this is not only relevant to piano playing; recordings of Chopin’s Nocturnes were also produced by singers, violinists, flutists, and cellists.

The lecture-recital is divided into three parts: Part 1 considers how various text-based sources serve to illuminate aspects of late nineteenth century pianism in context of Chopin’s Nocturnes. Part 2 considers various recordings of Chopin’s Nocturnes, made between 1890 and 1930. Analysis of these recordings is a part of the Leverhulme-funded research project “(Re)constructing Early Recordings: a guide for historically-informed performance”. The three year research project is based on the reconstruction and simulation of the mechanical recording process to capture performances using wax cylinder and digital technologies, and investigation of the value of reconstructions of passed recording techniques, in terms of preserving forms of performance practice. A broad range of expressive pianistic techniques are then showcased in Part 3, through a performance which clarifies and contextualises central points of this lecture-recital.

Proceedings of ‘Doctors in Performance’ Conference, Vilnius

This article introduces the practice of historically-informed recording. It starts by offering a brief definition of this practice before providing an outline of a working method used to produce historically-informed recordings. The paper goes on to introduces a particular example of this practice, in which the authors recreated four historic recordings originally made by amateur recording pioneer, Julius Block. In following the stated method, musicological research into Block’s technologies and recording techniques was supplemented with practical experimentation with a range of phonograph machines and associated technical equipment. In doing so, the authors explain how various phonograph makes and models, recording horns, cutters, wax cylinders, performance styles, instruments, and many more associated factors need to be taken into account when recreating early phonograph recordings. Attention is directed towards the notion of the historically-informed, and while the authors attempted to discover as much as possible about Block’s original recordings, most of the significant discoveries involved experimentation and testing rather than musicological research. The findings of the article are subsequently varied; although significant question-marks over the historical efficacy of the recreations remain, discoveries about the various phonograph machines, and their ability to record musical performances, demonstrate the relevance of historically-informed recording as a practice. More research is needed, and a range of pertinent areas for future exploration are offered.

Seismograf. Sounds of Science. Methods and Aesthetics in Auditory Research Practices

This article considers the reception of Frédéric Chopin in Great Britain, between the years 1849 and 1899. It serves as a natural sequel to “Love me, love me not (Part I): Chopin’s reception in Great Britain, 1830–1849” (Musica Iagellonica, 2019). Chopin’s reception in nineteenth century Britain is complex, resembling a colourful patchwork of sources placed in various social, cultural, and economic contexts. Unlike reception during his life, which was polarised, colourful, and unpredictable, reception following his passing in 1849 is much less turbulent and improbable, while still involving nu- merous preconceptions, subtexts and misrepresentations established during Chopin’s lifetime. In exploring the gradual reinforcement of Chopin’s position in the second half of nineteenth century Britain, we see that the popularity of a composer is not eas- ily gained; in Chopin’s case, we witness a gradual build-up of his popularity, alongside interest and representation in the press. This article presents the various steps towards an ultimate acceptance for Chopin as a composer at the end of the nineteenth century Britain.

Article in: Musica Iagellonica, Vol. 11, 2020. ISSN 1233–9679

This article considers the reception of Frédéric Chopin, both as a pianist and composer, in Great Britain during his lifetime. Examination of British attitudes to Cho- pin between 1830 and 1849 reveal an exceptional position in reception history; even though Britain was one of three locations for publication of his first editions, the po- larised reactions to Chopin’s music greatly influenced the reception and performances of his works after his death, ultimately revealing a different set of attitudes to those exhibited in France and Germany. Much of the material presented in this article is relatively unknown, and in presenting press attitudes to Chopin during his lifetime, we can trace how British critics reflect debates going on the Continent. Understanding how the press represented and viewed Chopin during his life time, help to build a picture of various tropes that developed later in the nineteenth-century.

Book chapter in: The Great War 1914-1918 and Music. Compositional Strategies, Performing Practices, and Social Impacts (Hrvatsko Muzikološko Društvo; Zagreb)

In the digital age, reproducing piano rolls are increasingly hard to hear; the original playback technologies are rare, and many have deteriorated since their construction. Thankfully, a vast archive of digitisations has enabled performances, captured on such rolls, to become increasingly available for use within musical research. These digitisations preserve historic performance practices that have, in many cases, since disappeared from use and, as a consequence, they have an extremely valuable role to play in numerous research fields. The nature of this role may, however, be questioned; digitisations are often taken to be primary sources of evidence, seemingly offering direct and immediate access to once-upon-a-time performances. The processes involved in their production, however, suggest that they may be more appropriately understood as secondary sources. To demonstrate this point, this article offers a case study through which the production of digitisations is scrutinised; a range of visualisation tools are used to examine nine digitisations of a single piano roll and, although one may expect uniformity among the digitisations, visualisations reveal significant and substantial differences. Some of these differences may be attributed to the piano roll technologies, particularly in terms of the voicing and balance of the piano. Others are a consequence of the digitisation process itself; specific recording techniques, room acoustics, and microphone selection are but some of the many variables that determine the nature of the digital result. As the article develops, it becomes increasingly clear that digitisation profoundly influences what we hear. It is paramount that we understand the variables involved in the production of digitisations, since their capacity to take us back to the past ensures that they remain invaluable sources of evidence long into the future.

Article in: Swedish Journal of Musical Research/Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning, Vol. 99

Article in: HARTS & Minds Journal, Vol. 3, Issue 2 (Embodied Masculinities)

Proceedings of ‘Music, Sound and Culture (MUSICULT 2016)’, Istanbul, Turkey