Neglected tropical diseases research

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of debilitating, disfiguring, and sometimes deadly, infectious diseases affecting more than 1 billion people worldwide. NTDs are found mainly in tropical and sub-tropical countries and disproportionately affect the poor, often in marginalised communities and conflict areas. The disability and social stigma associated with NTDs can hamper people’s ability to work, attend school and thrive within their families and communities, impacting the development of the world’s poorest communities and countries.

What we are researching

We work on a range of bacterial, viral and parasitic NTDs including Buruli ulcer, intestinal worms and rabies, schistosomiasis and echinococcosis.

A key feature of NTD research at Surrey is cross-disciplinary working bringing together biologists, vets, mathematical modellers, engineers, psychologists and artists to address the challenges posed by NTDs. The One Health-One Medicine approach underpins our research.

We work with universities, research institutions, government ministries and NGOs in endemic countries across sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America. Building capacity in endemic countries to combat NTDs is central to our work.

Our work on NTDs is funded by UK and global funders including UKRI, Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Recently, the University of Surrey has joined the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research.

Buruli ulcer

Buruli ulcer, caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans, is a chronic, debilitating disease of the skin and soft tissue. The infection is “flesh-eating”, starting as a painless lump, but resulting in extremely large and disfiguring ulcers. These ulcers are usually painless so people often do not seek treatment until late stages of the disease. The bacteria make an oily toxin (mycolactone) that causes the pathology.

Although it is known that Buruli ulcer is acquired from the environment, rather than being spread from person to person, it is not clear how this happens. Buruli ulcer is common in resource-poor and inaccessible rural communities in West Africa. As other skin diseases such as leprosy are found in these areas, diagnosis of Buruli ulcer can be difficult. Although the disease can be treated with a long course of antibiotics, wound healing can sometimes take over a year.

At the University of Surrey we are:

- Developing improved diagnostic information based on medical illustrations which are better than photographs, in a unique collaboration between artists and scientists.

- Investigating the role of blood clotting pathways in the progression of the disease.

- Using mathematical models to explore interactions between the bacteria and host skin and thereby improve treatment.

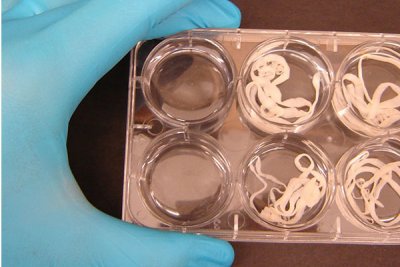

Intestinal worms

Intestinal worms (also known as soil transmitted helminths) are extremely common and widespread infections of people, particularly in children. Infections can cause intestinal problems, anaemia and stunting and wasting in children, and may even affect school performance. In areas with poor hygiene and sanitation, people become infected through ingesting worm eggs contaminating food or on their hands, or by worms direct directly penetrating their skin. Intestinal worm disease is controlled through regular treatment of people in endemic communities with deworming drugs. However, there are concerns about resistance developing to these drugs, sustainability of deworming programmes and whether deworming alone is enough to stop the spread of worms.

At the University of Surrey, we are:

- Determining the role played by animals and the environment in the spread of intestinal worms to humans.

- Investigating resistance to deworming drugs in intestinal worms.

- Developing new vaccine targets for intestinal worms.

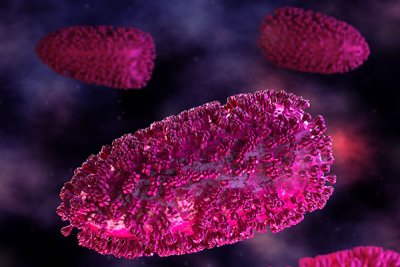

Rabies

Rabies is caused by a virus that is transmitted in the saliva of infected animals. The virus attacks the nerves and brain of its victims, and the disease is fatal once symptoms appear. Rabies kills one person every 10 minutes throughout the world. The most effective way to control rabies in humans is to control the disease in animals by vaccination. In many parts of the world, domestic dogs are a source of rabies but wildlife can be infected and spread the disease to dogs and humans. Rabies is difficult to eliminate as cultural attitudes to dogs and wildlife vary across the world, leading to misunderstandings which are barriers to control.

Rabies is a disease of poverty which does not respect cultural or political boundaries. In addition, rabies can spread easily from one species to another and remain for a long time hidden in the nervous system, complicating diagnosis. Better diagnostic tests with improved communications and data handling are needed.

At the University of Surrey we are:

- Investigating rabies spread and the most cost-effective approaches to rabies control using mathematical models.

- Studying how the virus transmits and adapts from one species to another neglected tropica disease.

- Contributing expertise to the United Against Rabies forum and the Middle East and East Africa Rabies Control Network.

Researchers

Dr Martha Betson

Associate Professor in Veterinary Parasitology and Head of Department

Biography

Martha graduated from University of Cambridge with a BA in Natural Sciences and went on to do a PhD in cell biology at University College London. She then undertook postdoctoral work at Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA, where she used the fruit fly as a model to gain insight into signalling pathways regulating cancer. While in Boston Martha developed an interest in public health and infectious diseases. After studying for an MSc in Control of Infectious Diseases at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, she worked as a postdoctoral researcher with Prof Russell Stothard, first at the Natural History Museum and then at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Here she played an integral role in the Schistosomiasis in Mothers and Infants project, investigating the epidemiology of a neglected parasitic disease in mothers and young children living in lakeshore communities in Uganda. Subsequently Martha took up a post as a research fellow in One Health at the Royal Veterinary College. Martha joined the School of Veterinary Medicine in May 2015 and became Head of Department of Veterinary Epidemiology and Public Health in 2019.

Professor Daniel Horton

Associate Dean Research and Innovation (FHMS), Professor of Veterinary Virology

Biography

Dan graduated as a veterinarian from the University of Cambridge, UK, with an intercalated MA in zoology in 2002. After a period in mixed and second opinion exotic animal veterinary practice he completed an MSc in Wild Animal Health in London in 2005. He then undertook a PhD working at Cambridge University, the APHA and CDC Atlanta USA, on zoonotic viral diseases of wildlife.

He completed his PhD in 2009 and joined the Virology Department at APHA Weybridge, undertaking surveillance and research programs for viral diseases of wildlife. Since February 2014 he has been at the School of Veterinary Medicine as a Lecturer, promoted to Senior Lecturer, Reader and then Professor of Veterinary Virology, continuing research into zoonotic viral diseases and teaching at undergraduate and postgraduate level. He is Associate Dean Research and Innovation for the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, an elected representative of Senate on the University Council, an Editor for PloS Neglected Tropical Diseases and a Diplomate of the European College of Zoological Medicine.

Dr Giovanni Lo Iacono

Senior Lecturer in Biostatistics/Epidemiology

Biography

Gianni is a theoretical physicist specialized in fluid dynamics with an initial background in particle physics. After his PhD at the University of Warwick he started to work at Silsoe Research Institute and then Rothamsted (two agricultural research institutes) studying the motion of aerosols in turbulent flows, searching strategy of insects and epidemiology of plant disease (evolution of pathogens in response to crop resistance).

Then he moved to the Veterinary School at the University of Cambridge working on vector borne diseases and zoonotic diseases. He then spent a few years in Public Health England focusing on the link between environmental changes and infectious diseases. In September 2017 he joined the School of Veterinary Medicine as lecturer in Biostatistics and Epidemiology.

Some measures of esteem

Several papers of mine have been cited in many policy documents, including documents from the WHO, CDC and the recent Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the United Nations.

My academic outputs have been cited multiple times in journals of exceptional level like including Nature, The New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Cell, Nature Communication, Nature Climate Change, PNAS.

I act as expert reviewer for many journals including: Nature Communication, Nature Climate Change, The Lancet Infectious Disease, The Lancet Global Health, The Lancet Planetary Health and Ecology Letters.

Dr Joaquin Prada

Co-Director Surrey Institute for People-Centred AI Senior Lecturer in Epidemiology

Biography

My research focuses on the development of mathematical and statistical models to inform policy decision-making for the control and elimination of infectious diseases, with a particular interest in neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

My work has supported global policy, for example during the development of the 2021-2030 NTD roadmap, and I am also part of several informal WHO-led working groups and the United Against Rabies forum working group 1 (a FAO-OIE-WHO initiative). My research group at Surrey combines mathematical modelling with economic evaluation and stakeholder elicitation techniques to develop sustainable portfolios of interventions against NTDs (in particular zoonotic NTDs such as Echinococcosis and Rabies).

I hold a visiting position at North Carolina State University. I previously held similar visiting positions at the University of Warwick and the University of Oxford.

Professor Rachel Simmonds

Professor of Immunopathogenesis

Biography

Research in my group focusses on the mechanism of action of mycolactone, the lipid-like exotoxin of the Buruli ulcer infectious agent, Mycobacterium ulcerans. Mycolactone has many unusual and fascinating biological functions, and in 2014 we identified its mechanism of action - as an inhibitor of protein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. We are now applying this knowledge to understand more about Buruli ulcer, a neglected tropical disease, and basic cell biology. In particular, I have a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award in Science to investigate how this mechanism underpins the role of disordered blood clotting in the pathogenesis of Buruli ulcer.

After graduating from the University of Manchester with a degree in Molecular Biology, I went on to study for a PhD with David Lane at Imperial College London. My early career was in haemostasis (regulation of blood clotting), with a particular focus on the protein C anticoagulant pathway and endothelial cell biology. I had a career break and then joined the Macrophage Biology group at the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology (Imperial College London), changing my research field to study inflammatory signalling. My first academic appointment here at the University of Surrey started when I recieved my first award from the Wellcome Trust.