Dr Sazana Jayadeva

About

Biography

Sazana is a Surrey Future Fellow based in the Department of Sociology. She is an Associate Editor of the journal Sociology, and an editorial board member of the journals Sociological Research Online and Global Networks. She co-convenes the International Research and Researchers’ Network of the Society for Research into Higher Education, and leads the Digital Societies research group at Sociology at Surrey. She is also affiliated with the GIGA Institute of Asian Studies in Germany as an Associate Researcher.

Her research revolves around the broad themes of education, migration, and digital and social media. Methodologically, she has expertise in qualitative research methods including interviews, ethnographies, and visual methods.

My qualifications

Affiliations and memberships

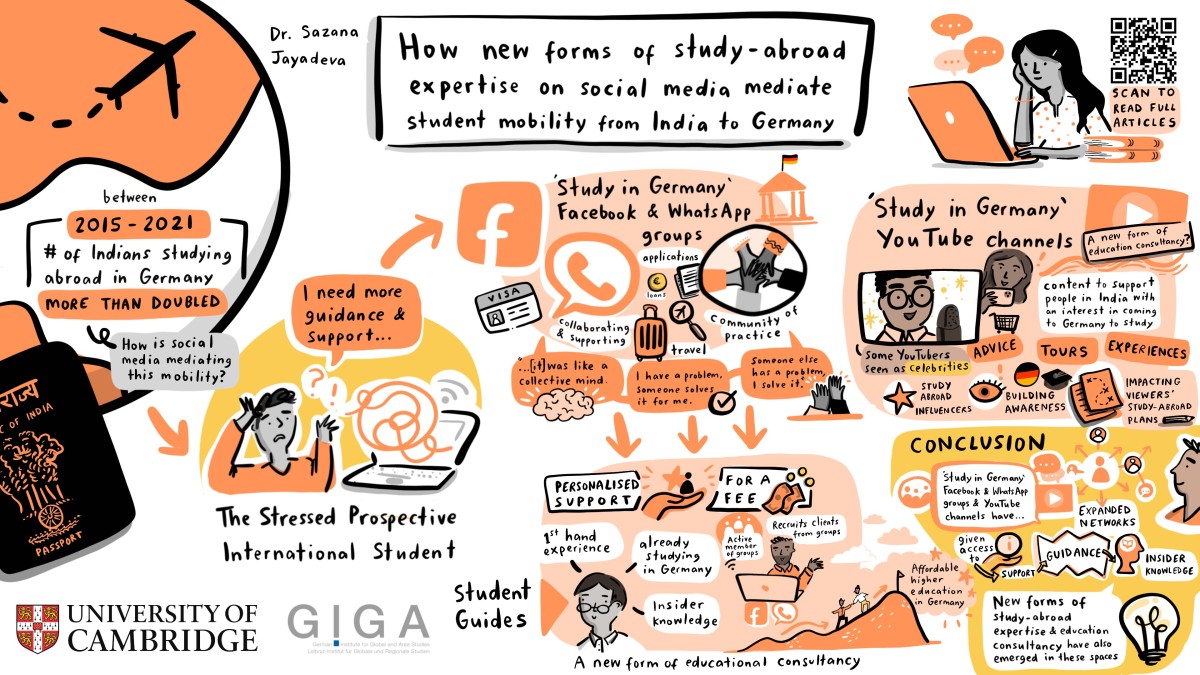

Recent research: How new forms of study-abroad expertise on social media media student mobility from India to Germany (illustrated by Katie Chappell)

News

ResearchResearch interests

My research revolves around the broad and interrelated themes of education, migration, language, social class, and digital and social media. Methodologically, I have expertise in qualitative research methods including interviews, ethnographies, digital ethnographies, and visual and creative methods.

At present I am involved in the following projects:

Project 1

Title: Virtual Mobilities of International Students (VIRMOBS): towards a new model for the internationalisation of higher education?

Principal investigator: Dr Valerie Erlich

Co-investigators: Dr Magali Ballatore, Prof Sylvie Mazzella, Dr Jean-Baptiste

Bertrand (France); Prof Cathia Papi, Dr Olivier Begin-Caouette, Mr Alexandre

Delong (Canada); Dr Aline Courtois, Dr Sazana Jayadeva, Prof Rachel Brooks (UK).

Funding: Open Research Area

Project 2

Title: Study-Abroad Influencers: the role of YouTube in mediating tertiary-level student migration from India

Principal investigator: Sazana Jayadeva

Funding: University of Surrey

Project 3

Title: Branding destiNATIONS for international higher education in Israel, South Korea and India

Principal investigator: Annette Bamberger

Co-investigators: Evelyn Kim and Sazana Jayadeva

Project 4

Title: Tracking Long COVID: A study of patients’ engagements with self-tracking technologies

Principal investigator: Sazana Jayadeva

Co-investigator: Deborah Lupton

Funding: University of Cambridge

Previously, I worked on the ERC-funded Eurostudents project, led by Prof. Rachel Brooks, which investigated how the contemporary higher education student is conceptualised by different social actors within and across six European countries. My doctoral research explored the central role that English language proficiency has come to play in middle-class formation in post-liberalisation India, through an examination of people's journeys to acquire proficiency in English both within and outside the formal education system, with particular focus on low-cost English-medium schools and commercial spoken English training centres targeting adults.

Research interests

My research revolves around the broad and interrelated themes of education, migration, language, social class, and digital and social media. Methodologically, I have expertise in qualitative research methods including interviews, ethnographies, digital ethnographies, and visual and creative methods.

At present I am involved in the following projects:

Project 1

Title: Virtual Mobilities of International Students (VIRMOBS): towards a new model for the internationalisation of higher education?

Principal investigator: Dr Valerie Erlich

Co-investigators: Dr Magali Ballatore, Prof Sylvie Mazzella, Dr Jean-Baptiste

Bertrand (France); Prof Cathia Papi, Dr Olivier Begin-Caouette, Mr Alexandre

Delong (Canada); Dr Aline Courtois, Dr Sazana Jayadeva, Prof Rachel Brooks (UK).

Funding: Open Research Area

Project 2

Title: Study-Abroad Influencers: the role of YouTube in mediating tertiary-level student migration from India

Principal investigator: Sazana Jayadeva

Funding: University of Surrey

Project 3

Title: Branding destiNATIONS for international higher education in Israel, South Korea and India

Principal investigator: Annette Bamberger

Co-investigators: Evelyn Kim and Sazana Jayadeva

Project 4

Title: Tracking Long COVID: A study of patients’ engagements with self-tracking technologies

Principal investigator: Sazana Jayadeva

Co-investigator: Deborah Lupton

Funding: University of Cambridge

Previously, I worked on the ERC-funded Eurostudents project, led by Prof. Rachel Brooks, which investigated how the contemporary higher education student is conceptualised by different social actors within and across six European countries. My doctoral research explored the central role that English language proficiency has come to play in middle-class formation in post-liberalisation India, through an examination of people's journeys to acquire proficiency in English both within and outside the formal education system, with particular focus on low-cost English-medium schools and commercial spoken English training centres targeting adults.

Supervision

Postgraduate research supervision

Current PhD students:

Aram Gholamian, Bettina Teegen, Jingyu Chen, Mokhidil Mamasolieva

Publications

Highlights

Bamberger, A., Kim, E., Jayadeva, S. (2026). Constructing national higher education brands: Korea, India and Israel Compared. European Journal of Education.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ejed.70428

This article examines how higher education (HE) students are conceptualised in Spain, drawing on an analysis of policy and institutional narratives about such students, as well as on the perspectives of university staff and students themselves. More specifically, it will explore an interesting paradox that we encountered in our data: on one hand, marketisation is less firmly established in the HE system of Spain than in many other European countries, and policy and institutional narratives in Spain present the HE system as being relatively unmarketised. On the other hand, the staff and students we interviewed presented the Spanish HE system and the student experience as having been dramatically transformed by marketisation. In analysing this paradox, the article highlights the importance of not viewing countries as coherent educational entities. In addition – while broadly supporting scholarship that has pointed to a growing market orientation of national HE systems across Europe – the article draws attention to how the manner in which the marketisation of HE is experienced on the ground can be very different in different national contexts, and may be mediated by a number of factors, including perceptions about the quality of educational provision and the labour market rewards of a degree; the manner in which the private cost of education (if any) is borne by students and their families; and the extent to which marketisation may have become entrenched and normalised in the HE system of a country.

Across Europe, assumptions are often made within the academic literature and by some social commentators that students have come to understand the purpose of higher education (HE) in increasingly instrumental terms. This is often linked to processes of marketisation and neo-liberalisation across the Global North, in which the value of HE has come to be associated with economic reward and labour market participation and measured through a relatively narrow range of metrics. It is also associated with the establishment, in 2010, of the European Higher Education Area, which is argued to have brought about the refiguration of European universities around an Anglo-American model. Scholars have contended that students have become consumer-like in their behaviour and preoccupied by labour market outcomes rather than processes of learning and knowledge generation. Often, however, such claims are made on the basis of limited empirical evidence, or a focus on policies and structures rather than the perspectives of students themselves. In contrast, this paper draws on a series of 54 focus groups with 295 students conducted in six European countries (Denmark, England, Germany, Ireland, Poland and Spain). It shows how understandings of the purpose of HE are more nuanced than much of the extant literature suggests and vary, at least to some extent, by both nation-state and higher education institution. Alongside viewing the purpose of HE as preparing them for the labour market, students emphasised the importance of tertiary-level study for personal growth and enrichment, and societal development and progress. These findings have implications for policy and practice. In particular, the broader purposes of HE, as articulated by the students in this study, should be given greater recognition by policymakers, those teaching in HE, and the wider public instead of, as is often the case, positioning students as consumers, interested in only economic gain.

This paper examines how the Covid-19 crisis is impacting Indians’ plans to study for a postgraduate degree in Germany, and how Indians currently studying in Germany have been affected. It draws on interviews conducted with Indian Master’s students in Germany and digital ethnographic research carried out within social media communities used by prospective students. The paper shows how, apart from concerns about a disrupted educational experience, prospective and current students were very concerned about the impact of Covid-19 on the German job market and the ability of an international student to secure a good job in their field of study upon graduation. The paper explains why, despite these concerns, most prospective students do not appear to be rethinking their plans to study in Germany. However, they are facing major hurdles in applying to universities, obtaining visas, and organising travel, as a result of lockdowns in India and international travel restrictions. These logistical problems might lead to a fall in postgraduate student flows from India to Germany this year.

Drawing on data from students, higher education staff and policymakers from six European countries, this article argues that it remains a relatively common assumption that students should be politically engaged. However, while students articulated a strong interest in a wide range of political issues, those working in higher education and influencing higher education policy tended to believe that students were considerably less politically active than their predecessors. Moreover, while staff and policy influencers typically conceived of political engagement in terms of collective action, articulated through common reference to the absence of a ‘student movement’ or unified student voice, students’ narratives tended not to valorise ‘student movements’ in the same way and many categorised as ‘political’ action they had taken alone and/or with a small number of other students. Alongside these broad commonalities across Europe, the article also evidences some key differences between nation‐states, institutions and disciplines. In this way, it contributes to the comparative literature on young people’s political engagement specifically, as well as wider debates about the ways in which higher education students are understood.

This paper draws attention to the increasingly central yet understudied role of social media in facilitating student mobility from India. More specifically, it explores the emergence of online mutual-help communities of aspirant student migrants on Facebook and WhatsApp, which are aimed at helping members navigate the process of going abroad for study. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork focused on postgraduate-level student migration from India to Germany, the paper explores how these communities are meeting aspirant student migrants’ information and support needs in novel ways. Not only are they a key space in which information on study in Germany is discussed, dissected, and interpreted, they have also resulted in the production of a whole new body of information, tools, and resources on how to navigate the process of going to Germany for a Master’s degree. The paper argues that these communities can be seen as democratising access to study abroad, to some extent, by dramatically expanding applicants’ social networks and the social capital to which they have access.

Focusing on low‐cost English‐medium schools, this article investigates whether the ideology of the transformative potential of English‐medium education squares with most people’s experiences of this education in urban India. It shows how such schools enable socioeconomic mobility among the middle classes while also creating new forms of inequality. It argues that a meaningful evaluation of education outcomes requires understanding students’ and their parents’ experiences of an education system and its impact on their lives.

Anthropological studies of India's post-liberalization middle classes have tended to focus mainly on the role of consumption behaviour in the constitution of this class group. Building on these studies, and taking class as an object of ethnographic enquiry, I argue that, over the last 20 years, class dynamics in the country have been significantly altered by the unprecedentedly important and complex role that the English language has come to play in the production and reproduction of class. Based on 15 months of ethnographic fieldwork—conducted at commercial spoken-English training centres, schools, and corporate organizations in Bangalore—I analyse the processes by which this change in class dynamics has occurred, and how it is experienced on the ground. I demonstrate how, apart from being a valuable type of class cultural capital in its own right, proficiency in English has come to play a key role in the acquisition and performance of other important forms of capital associated with middle-class identity. As a result, being able to demonstrate proficiency in English has come to be experienced as a critical element in claiming and maintaining a space in the middle class, regardless of the other types of class cultural capital a person possesses.

This article draws on data from six European countries (Denmark, England, Germany, Ireland, Poland and Spain) to explore the higher education timescapes inhabited by students. Despite arguments that degree-level study has become increasingly similar across Europe – because of global pressures and also specific initiatives such as the Bologna Process and the creation of a European Higher Education Area – it shows how such timescapes differed in important ways, largely by nation. These differences are then explained in terms of: the distinctive traditions of higher education still evident across the continent; the particular mechanisms through which degrees are funded; and the nature of recent national-level policy activity. The analysis thus speaks to debates about Europeanisation, as well as how we theorise the relationship between time and place.

This paper explores how university staff in Denmark, Germany, and England perceived higher education (HE) policy as impacting the experience of being a student in their respective countries. While, in each nation, different policy mechanisms were identified as having triggered transformations in the experience of being a student, the transformations themselves were described in a strikingly similar manner across all three countries: staff stressed that students had become more instrumental in their approach to learning; that the student experience had become more circumscribed; and that students were under greater stress. We analyse how staff’s narratives about the impact of policy on the experience of being a student were mediated by their own ideas about what constituted ‘good education’, which in turn were strongly rooted in national traditions. Furthermore, in each country, staff’s assessment of the impact of specific policies on HE differed sharply from those of policy actors. Our findings contribute to the scholarship on the marketisation of HE, through drawing attention to how the rationality underpinning policy does not determine how it is engaged with by key stakeholders on the ground, and by demonstrating how the neoliberalisation of HE can unfold in different formats, some more explicit than others.

There is a growing body of scholarship on how students see themselves, and also on how they are conceptualised by other social actors. However, what has been less explored is how students believe they are seen by others, and how this impacts them. Drawing on focus groups with students across Europe – and particularly plasticine models students made to depict how they felt they were seen by relevant others – this paper will illustrate how the four most common ways in which students felt they were constructed were as hedonistic and lazy; useless and a burden; clever, hardworking, and successful; and a resource to be exploited. It will argue that such stereotypes had significant material impact on students’ lives and how they experienced being a student. Finally, it will analyse how specific national contexts accounted for a range of variations in how students articulated these constructions.

This paper examines new forms of study-abroad expertise on social media and their role in mediating Indian student mobility to Germany. Firstly, it explores how mutual-support Facebook and WhatsApp groups—used by prospective international students in India to support each other through the process of applying to German universities—have contributed to the emergence of new forms of education consultancy, offered by Indian students or graduates of German universities, whom I call ‘Student Guides’. In addition, it shows how some Indians studying in Germany have started ‘Study in Germany’ YouTube channels, aimed at aspirant student migrants, and have become important ‘study-abroad influencers’. The paper analyses how these new forms of study-abroad expertise offer prospective international students social and cultural capital important for successful student migration, apart from shaping their imaginative geographies of Germany, and embedding them in cultures of mobility. Furthermore, the paper highlights how these new forms of study-abroad expertise intersect with, and critique, a more ‘traditional’ study-abroad expert: the professional education consultant. The paper draws on a digital ethnography of ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups and YouTube channels, as well as interviews with the YouTubers, Student Guides, and Indian students in Germany.

While there is now a relatively large literature on young people's aspirations with respect to their transitions from compulsory schooling, the body of work on the aspirations of those within higher education is rather less well-developed. This article draws on data from undergraduate students in six European countries to explore their hopes for their post-university lives. It demonstrates that although aspirations for employment were discussed most frequently, non-economic plans and desires were also important. Moreover, despite significant commonalities across the six nations, aspirations were also differentiated, to some extent at least, by national context, institutional setting and subject of study.

This special issue focuses on the concept of the ‘ideal’ higher education student. It explores how this concept is played out in different national contexts and the implications it has for particular groups of students and their experiences within higher education. In this editorial introduction, we introduce the seven papers that make up the special issue, and then discuss some of the cross-cutting themes – showing how the papers help to advance our knowledge in this area.

The capacities of aspirant student migrants to negotiate the process of going abroad is closely linked to their economic, social, and cultural resources. Based on fieldwork in India and Nepal, we explore the contested role of commercial education consultants in supporting aspirant student migrants to access study abroad. Drawing on interviews with international students and an analysis of the conversations about education consultants within online communities of aspirant student migrants, we highlight how consultants are discussed as being powerful agents that guarantee a safe path to studying abroad, while also, being decried as profit-driven actors. We then move to the perspectives of the consultants themselves, how they experience the application process and engage with their ambivalent reputation. In doing so, the chapter explores how access to study abroad is negotiated and how this often involves ‘co-learning’ and ‘co-work’ between aspirant student migrants and consultants.

People living with Long COVID are dealing with significant challenges related to limited understanding of this novel condition, social stigma, and lack of support from medical professionals and others in their lives. This article discusses findings from a qualitative study about how people with Long COVID have spontaneously engaged in self-tracking for the purposes of understanding and managing their illness. It draws on 30 semi-structured interviews with study participants in the USA, UK, Australia, Germany, Denmark and Canada. The study’s findings reveal that the personal health data generated by people with Long COVID through practices of self-tracking create new forms of knowledge about a novel post-viral condition and to some extent challenge the power differentials and fraught sociopolitical climate of the pandemic. The benefits provided by self-tracking data reflect the often psychologised and understudied position of post-viral conditions such as Long COVID. All participants described self-tracking as a valuable tool to gain insight into symptoms and evaluate interventions. It provided them with a sense of empowerment, control, encouragement, and very importantly, validation. However, for some participants, self-tracking their Long COVID symptoms was also sometimes experienced as overwhelming, anxiety-inducing, and frustrating. The study findings are interpreted with references to the broader contexts of novel chronic illness, medical power, lay expertise, COVID politics and digitised information and care work.

This article examines the rising postgraduate-level student migration of Indian engineers to Germany, drawing on interviews with 42 Indians who were applying to, currently pursuing, or had recently graduated from engineering Master’s degrees in Germany. It illustrates how the affordable cost of study in Germany had made postgraduate study abroad a feasible strategy for the study participants to escape the unfavourable job market for graduates of engineering undergraduate programmes in India, and attempt to realise their professional ambitions through acquiring post-study work experience at German engineering companies. Such work experience was viewed as having greater social currency in the Indian engineering job market, where most wished to return eventually, than overseas education credentials. Moreover, the article demonstrates how imaginings of Germany as an engineering superpower underpinned the value associated with gaining engineering work experience in the country. This case study shows how in contexts where international students anticipate that the portability of overseas education to a target labour market is uncertain, post-study work experience may be viewed as a safer form of cultural capital to accumulate. Acquiring post-study work experience abroad may then not just be a way to supplement overseas education credentials, as described in existing literature, but the primary motivator of study abroad. It also highlights how, in such contexts, place-based markers of distinction related to a country’s reputation in a particular occupational field can be more relevant in attracting international students than markers of distinction associated with the quality or prestige of its higher education institutions.

This article focuses on the struggles of people with Long COVID to obtain diagnoses and treatment in the face of medical dismissal and ignorance. Drawing on interviews with people with Long COVID who have engaged in self-tracking activities, it illustrates how these practices proved a valuable, if not completely successful, way to challenge medical dominance and epistemic privilege in relation to this contested illness. Furthermore, study findings demonstrate the important yet understudied role of online Long COVID patient communities in supporting self-tracking. The capacity for sharing patient-generated information through these communities offers a way for collective knowledge and interpretive resources to be amassed that can support communities of practice and mitigate hermeneutical injustice. The article contributes to scholarship on the role of digital apps, devices and communities in the generation and distribution of lay knowledge relating to Long COVID, as well as to the sociology of diagnosis and contested illnesses.

This study examines the websites of the national higher education (HE) brands of Study in Korea, Study in India and Study in Israel, exploring how these ‘offbeat’ destinations position themselves in the global HE market. Drawing on rhetorical analysis and employing a qualitative comparative case study approach, it reveals the key identity markers and rhetorical strategies employed in each campaign, considering temporal shifts. While these brands share some standardised elements, we suggest that these formats are deployed for different strategic reasons and articulated through varying rhetorical appeals, which may shift over time. We argue that for ‘offbeat’ destinations, nation branding in HE is more than a technocratic marketing tool to exploit niches in a highly competitive, multipolar global HE landscape; it is also a reflection of how states conceptualise their role therein and the value they attribute to international students in advancing national goals.