Life as a Battersea student during World War Two

Battersea Polytechnic Institute alumnus Harold Rowling – who celebrated his 100th birthday in February this year – tells us about student life in London during the Second World War…

Battersea Polytechnic, which was the forerunner institution to the University of Surrey

What attracted you to study at Battersea?

I lived my early life in south-west London. Battersea Polytechnic was well-known for its higher education science and engineering courses, modest fees and as a route to a London University degree.

My grammar school encouraged my father to apply for a place at Cambridge for me. But with three wives and seven sons to support on a retired teacher’s pension, it wasn’t possible. My ambition was focused on securing a BSc from London University and Battersea was foremost in my mind.

Can you tell me about your course?

I didn’t want to be financially dependent on my father, so I took employment as a chemist at Fulham Thameside gas works. In 1940, I started studying at Battersea for a degree via evening classes. This usually took six years.

I started – to my surprise – with a course in physics. The lecturer was an FRS. This was the highest qualification a scientist could achieve. I was impressed.

Eventually, I was able to obtain a State Bursary enabling me to study for a full-time degree. This was also tenable at Cambridge, but I chose to stay at Battersea. I changed my course to chemical engineering, then changed again to straight engineering.

Were there female students at Battersea then?

There were very few, except for a well-segregated minority wearing the blue uniform required for the domestic science course.

What was student life like during World War Two?

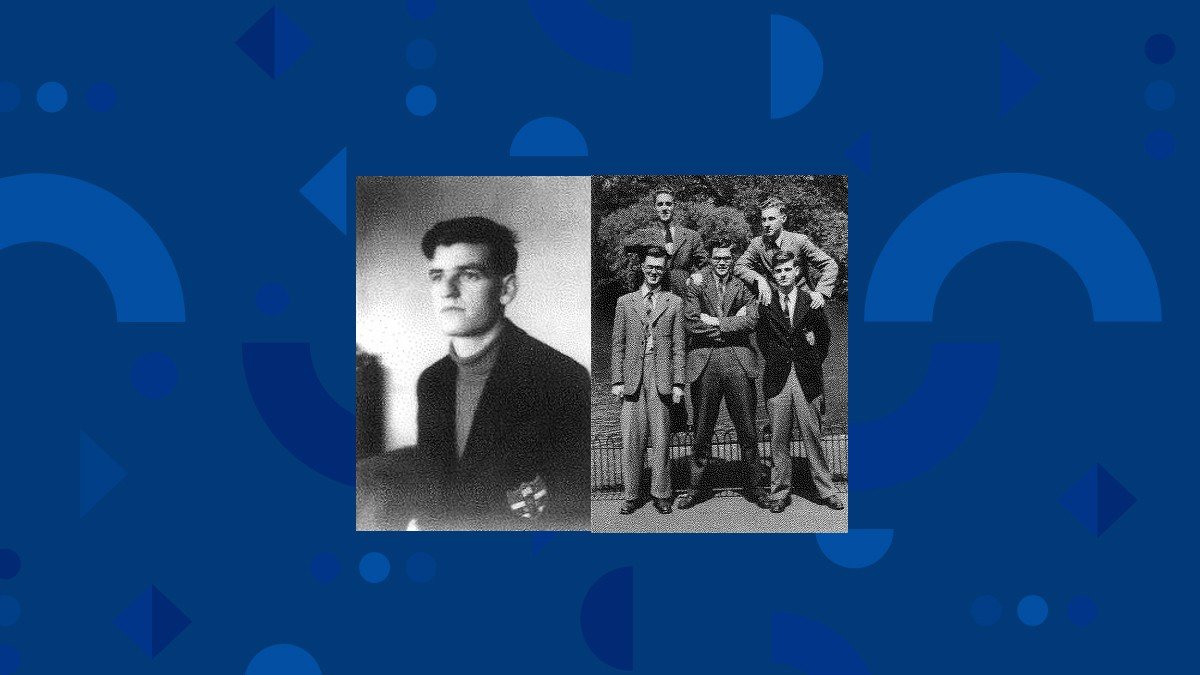

Harold (left) and Harold with four fellow Battersea students (right)

During 1941, there was a daily apprehension of invasion by the German Army.

Life was further dominated by the nightly air raids. After the final lecture of the day, most students hurried away from Battersea to the relative safety of their suburban homes.

I was in lodgings just a short bus ride away from the Polytechnic. I have severe claustrophobia, so I couldn’t go down into the air-raid shelter. The benefit of this was that I had more time to study. But I was young and wartime conditions were just part of life.

Life as an undergraduate was dominated by work required to complete the course in two years instead of the normal three. If you failed the end-of-term exam, you had to leave and you’d be in a khaki uniform within three weeks.

At the time, I felt guilty about being able to study while most men of my age were in uniform. Of the 30 boys in my form at school, only 15 were alive when hostilities ended in September 1945.

Did you still enjoy your course?

I very much enjoyed my new world of engineering. I’ve never regretted making the switch from the pure science of chemistry.

After two years of hard work – and probably due to the absence of female students to distract me – I achieved a BSc Eng (Lond) with First-class Honours. This was an excellent qualification in those days.

Can you tell us about your World War Two service?

Just a few weeks after my Finals, I became a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force (RAF), receiving further training as an engineer officer. At Battersea, I was taught to design a bridge with a 10 times safety factor and one-inch diameter BSW bolts. At the RAF, I found myself on an airfield servicing aircraft built with a 10 per cent safety factor and 2 BA (one eighth of an inch diameter) rivets. The figures were different, but the engineering principles were the same.

Did you see service overseas?

I was posted to India as part of the build-up for the onslaught on the Japanese army in the jungles of Burma. As the most junior and recently qualified engineer officer, I was put in charge of towed gliders. Each carried 20 soldiers into clearances in the jungle behind enemy lines. Little engineering knowledge was required – just skilled carpentry.

The real enemy wasn’t the Japanese – but the voracious tropical termites. The casein glue that fixed the wings to the fuselage was manna from Heaven for them. The attachment would rarely last longer than 48 hours before the wings fell off.

The atomic bomb brought the conflict to an abrupt end. It saved the lives of many thousands of servicemen – mine probably included.

What did you do after World War Two?

I worked in engineering research and development in the field of high intensity pressurised combustion. This was a new field due to the advent of the jet engine and subsequent industrial gas turbine developments.

Examples of my work are in the Science Museum in London, prominently in the Rover gas-turbine-powered car. My young daughter memorably told her fellow pupils that: “Daddy’s in a museum!” I also designed the combustion system for the first marine-gas-turbine-powered tanker.

I moved my work to investigate the after-effects of combustion and wrote a paper for the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. For this, I was awarded the Thomas Hawksley Gold Medal, the Institution’s highest award.

I enjoyed a lifetime of work in engineering research and development, with occasional diversions into other fields. I’ve had a very satisfying working life.

And it all started at Battersea in the dark days of 1941 when I had no engineering knowledge or inspiration. I was just a simple chemist back then.

Finally, what’s your proudest achievement?

I’m now 100 years old and the holder of an MBE. But the proudest moment of my life was to obtain a first-class honours degree from Battersea in a fascinating subject that was – mistakenly – not taught at my school. It changed my life.