An interview with Danielle Kurtin

Danielle completed her Learning and Teaching Graduate Certificate at Surrey in 2022. She is now a Research Associate in the Department of Brain Sciences at Imperial College London.

How did you decide to study at Surrey?

It was a bit of a “I found Surrey and Surrey found me” situation. I was doing my Masters in Translational Neuroscience at Imperial College London, and I asked every lecturer that I thought was interesting if they had any PhD positions or funding I could apply for. As an international student, it was something prominent in my mind, even from the early days of the Masters.

After talking to Dr Ines Violante after a lecture, she was supportive of my research goals. She helped me write an application for the Vice Chancellor’s studentship – one of the few available to international students. My application was successful, and to this day, I am grateful to Ines and to Surrey for their support.

Were you on campus a lot during your PhD?

I lived in London, so went to campus about 2 to 3 times a week, mostly to visit the lab. Ines did a great job of cultivating a good lab environment. Professor Jane Ogden was the Postgraduate Research director at the time, and she made a lot of effort to build a strong research community.

Could you talk a bit about the research you worked on at Surrey?

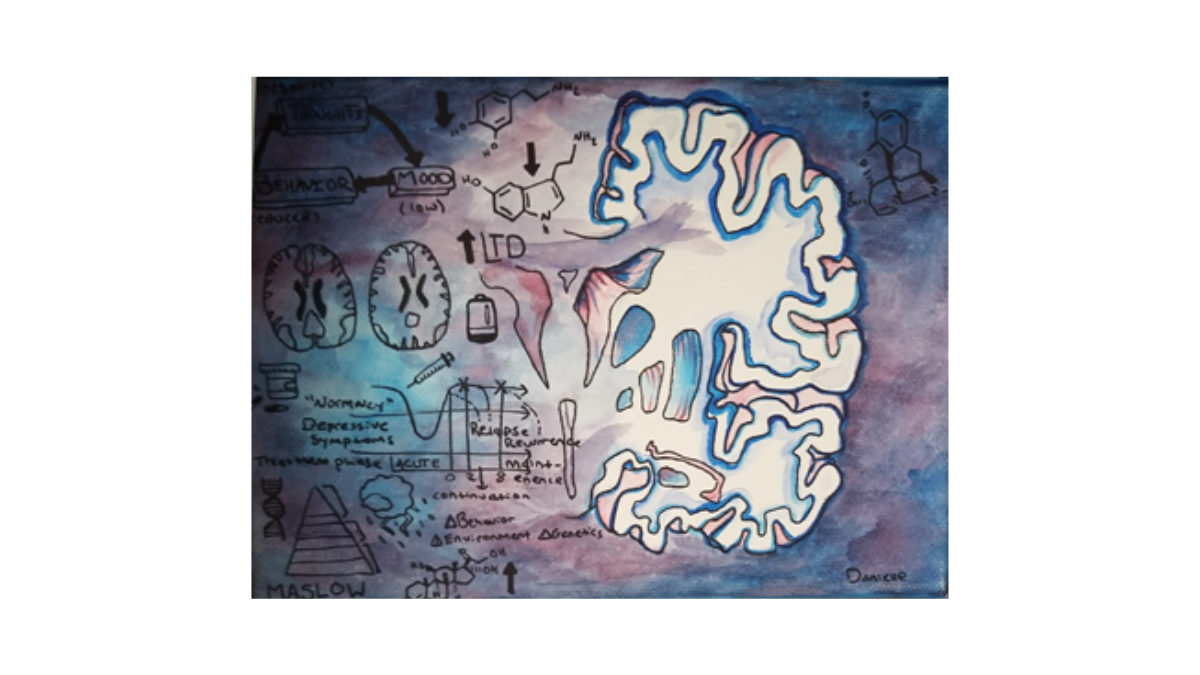

My interest that brought me to Imperial College was brain stimulation - using electricity to change brain function, or rather dysfunction, during different pathologies or psychiatric conditions. Imperial expanded my understanding of the diversity of brain stimulation and neuroimaging modalities. Neuroimaging is an extremely useful tool to characterise how the brain organizes information over space and time in healthy brains, and how patterns of brain function go awry people with neurological or psychiatric conditions.

At Surrey, I worked with both Ines and Professor Anne Skeldon to advance the methods by which we characterise brain functions. Nowadays, I build on this methods-focused computational work, and investigate the relevance of these techniques in a biological context - are they just fancy methods from physics and system dynamics, or can they provide meaningful, clinically-relevant insights?

How did you find that area of interest?

It started during my Masters when learning about a neuroimaging technique called functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI).FMRI is useful for identifying which brain regions engage with tasks performed in the scanner, or when people are resting. Initially, I conducted standard analyses that characterise the brain activity. However, this approached lacked the ability to assess how brain regions coordinate to execute the many complex, parallel functions the brain exhibits at all times. I thought about how brain regions are like people; they don’t work in isolation. Brain regions must communicate with each other, and it is very rare that you have a brain region that is purely for one function in the real world. I became curious about why we study the brain in an isolated way, and started studying how brain regions work together to form networks. Networks tend to subserve a particular neural processes, such as reward, cognition, attention, etc. Once you can define networks, you can then assess how networks interact with each other, and so on! Surrey gave me the opportunity to develop the skills necessary to conduct this research.

I can’t begin to think where you’d start with work like that!

It was not intuitive to me either! I had a biology and public health background, and at the time, was not fond of maths. That's why Anne Skeldon, a Professor in Mathematics, was such an important figure during my PhD. She made maths approachable, and I fell in love with it. The more questions I asked about the brain, the more they were answered in the language of maths – and it’s a language I enjoy learning more about to this day.

Could you talk about some other key learnings from your time at Surrey?

At Surrey I learned a lot about conducting open research. Marta Topor was a fellow PhD student when I arrived, and she had started the Surrey Reproducibility Society with the aim of promoting and teaching people to conduct open and reproducible research, particularly early career researchers. It started as a grassroots initiative, but with the help of Professor Emily Farran, and the university itself, open research became more entrenched in research across the university. As someone who participates in activism, it was amazing to be a part of this process - it's very rare that the things for which I protest and volunteer for get made into policy!

Could you talk a bit more about what open research means?

Open research refers to how can every step of the research ecosystem and process be made more reproducible. Reproducible and replicable research go hand-in-hand, and refer to results that withstand general retesting. Recently, psychology and psychiatry experience a reproducibility crisis. People were repeating previous studies and reporting different results, or results without significance, leading to mistrust in published studies and the research process. Open research invites us to take a hard look at the intersection between science and research culture, and how this influences scientific practice. For example, scientists may be influenced by a “publish or perish” mentality. Rewarding academics based on the number of papers they publish creates misaligned incentive with good scientific practice – one is encouraged to take a “quantity over quality” approach to papers, , emphasize results that are “better” because they are statistically significant, and ignore null results.

While some of open research focuses on scientific culture, individuals can support open research by sharing data and code. Sharing code has multiple benefits. For example, if your code is used for another study and your results replicate, it makes both sets of analyses more robust. Additionally, sharing code saves time. Since a lot of science is publicly funded, it’s in everyone’s interest to conduct studies robustly and efficiently .

Finally, open research works to overcome historical biases and barriers in research. Diversity is a sign of strength in both environmental and research ecosystems, so it is important to champion diversity in where research is conducted, the methods employed, or the means by which findings are shared.

Is open science connected to the activism you were involved with in the USA?

My passion projects are inseparable from my academic job, and I’ve always had a penchant for working for and with underserved communities. Whether through independent volunteer work or in partnership with the Red Cross, Martin Country Department of Health, or other institutions, I worked to support underserved communities, such as people without stable housing, migrants, or women in high-risk environments.

It was jarring to move from “boots on the ground” work, where I interacted with people in a very personal way, to computational research. However, I found ways to use my experience and education to continue my outreach, whether that was as a Trustee for UniArk (an educational charity in the UK), or more recently, as a co-founder for the podcast Craving Clarity. Craving Clarity aims to dispel myths and share current addiction neuroscience, while featuring the research and voices of people historically underrepresented in research environments.

Each episode takes a different angle, such as genetics, sociology, pharmacology, policy, and more! Craving Clarity is a unique opportunity to combine my research on substance (mis)use/dependence with the practice working to make research relevant and accessible for everyone, not just academics. . It's also great fun! The team has grown from four founders – Hajer, Brianna, Ayan, and myself – to include Ala and Qas. Qas is someone with lived experience with substance misuse, and his invaluable contributions really hammer home the value of including the people you’re talking about in your research, outreach, or policy. It’s living the “nothing about us without us” mentality.

How did you find moving from an academic sphere into public engagement like podcasts, where listeners may not have prior knowledge?

At first, I definitely had the habit of slipping into jargon, which can be alienating – or boring! Communication is a skill I am continually developing. I feel that if I can’t explain something clearly and simply, I probably don’t know it very well. I also try to harness my innate enthusiasm to convey that science is for everyone, and that everyone can find something interesting about science! Luckily, most people tend to find neuroscience interesting and relatable, given that we all have brains which often confound us!

I want to acknowledge that my ability to conduct this work is due to Surrey’s support of my research journey. My PhD formed the essential bridge between my background in public health and the computational, neuroimaging research I conduct today.

Do you have any advice for students looking to continue in academia or identifying their interests?

If you aren’t sure what you’re interested in, cast a broad net. Don’t worry about “wasting time” on interests that don’t work out; so many of my seemingly irrelevant experiences in waitressing, camping, or activism somehow benefit me to this day. But once you find something that interests you, and you want to commit to researching it further, I think there are two important points to consider. The first is whether you are interested enough in your research topic that you want to wake up every day for the next few years and keep working towards it. Second, find a good supervisor, whatever that means to you. Ines played a vital role in showing me how to conduct considered, methodical research – a skill I am still working on! You might need a supervisor who’s more hands on, or who’s less involved, or you might want someone who’s very friendly and personable, or someone who is more removed and professional. I really encourage students to think about what type of relationship they want with their supervisor, as this impacts so much of your PhD experience.

You can listen to Danielle’s podcast, Craving Clarity here: https://www.cravingclarity.co.uk/