“I’d like to be remembered as a confident, motivated and self-demanding woman”

To celebrate International Women’s Day – and as part of our Year of Surrey Women in Science and Engineering – Angela Danil de Namor, our Emeritus Professor in Physical Chemistry, discusses her journey from undergraduate mother in 1960s Argentina to distinguished academic.

You studied in 1960s Argentina as a part-time undergraduate and a full-time mum. How you did juggle that workload?

I married a few months after finishing secondary school, but I always planned to have a career. Back then, it was unusual for a married woman with children to pursue any role in biochemistry.

Fortunately, I was a determined youngster who’d spend hours through the night and in the early morning studying. When dawn came, I’d rush from home to the university to attend lectures and practicals. I always had the support of my husband, too, for which I’m grateful.

Why did you come to Surrey in 1970?

Initially, I was reluctant to go abroad. I was starting a doctorate in Argentina when my husband received a British Council scholarship for an MSc in Food Engineering at the University of Reading. With the support of my university in Argentina, I came to Surrey.

After a few months, I was offered a scholarship to proceed with doctoral studies at Surrey and I decided to stay. My husband also pursued PhD studies at Reading.

You were a student when Daphne Jackson became the first female Professor of Physics in the UK in 1971. Did you know her?

I met Daphne in 1977 when I started to teach chemistry on the MSc in Medical Physics. She was also a Member of the Board when I was appointed Lecturer in Chemistry in 1984.

She was confident, driven and always ready to support women. She was a remarkable person.

What were the key challenges facing female academics in the 1970s?

When I first arrived at Surrey, there were only two female postgraduates and two academics in chemistry. But the 1970s brought the Women’s Liberation Movement to the UK and things slowly changed.

The situation has improved today. But percentages of female students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects are still low. Also, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry, only nine per cent of chemistry professors in the UK are female.

As Assessor for the L’Oreal-UNESCO Prize for Women in Science, though, it’s encouraging to see the impressive CVs and high-quality proposals submitted by young female chemists in this country. Also very promising are my young fellow female academics in the Department of Chemistry.

You became Surrey’s first female Professor of Chemistry in 1999. What did that mean to you?

The Vice-Chancellor believed any promotion to Reader or Professor should be externally assessed by international experts, with no internal intervention.

I was delighted to have been promoted under that system. It meant a lot for me. It reinforced the international recognition of my research.

Who have been the influential or supportive women in your career?

Angela describes Daphne Jackson (pictured above) as a "remarkable person" who supported her

There have been many:

- Miss Laurie Gould, the University’s Personnel Director, helped me secure my permanent UK residence in the 1970s.

- Professor Daphne Jackson rectified the situation when she became aware I was a Research Officer with heavy lecturing duties in the late 1970s.

- The late Dr Teresa Poole was a lecturer in chemistry who helped promote my research.

- Dr Maria Kayamanidou endorses my role as Member of the Panel of Experts for evaluation of Proposals in EU Framework Programmes.

- Mrs Zeina El Eid from Lebanon gave me financial support for my cancer research.

What’s been your greatest achievement so far?

To concentrate on research leading to high-quality papers. This is the reason I’ve been invited to give plenary and keynote lectures at national and international conferences, and secured funding from industry and international bodies.

Is there a female scientist whose work continues to inspire you?

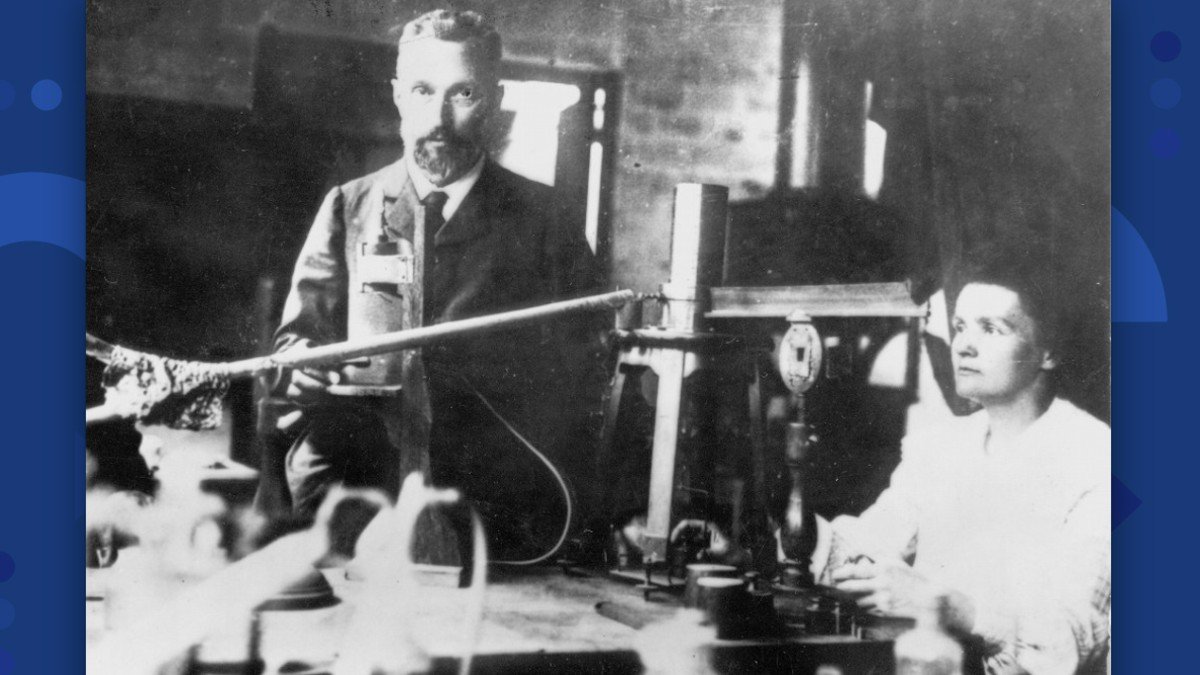

Double Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie in her laboratory with her husband, Pierre

The most inspiring figure for me was male – my father.

In science, however, I’m inspired to read about the challenges faced by outstanding women in chemistry. Marie Curie, who was awarded two Nobel Prizes in a totally male-dominated society, was fascinating.

Currently, I’m inspired by Jennifer Doudna. She jointly won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last year and showed a steely determination to protect her work.

In my opinion, however, gender shouldn’t be an issue in science.

How can we encourage more women to study STEM subjects?

New initiatives are required in primary and secondary education. Parents should be encouraged to motivate girls at an early age to become interested in STEM subjects, given the tools available to do so.

What legacy do you hope to leave for the next generation of women scientists?

I’d like to be remembered as a confident, motivated and self-demanding woman, who became a successful scientist, enjoyed an equally successful family and looked presentable.

As someone whose core belief was that in order to make a difference – in any sphere – results needed to exceed expectations. And as someone whose determination drove her to meet challenge, obstruction and adversity by being highly resilient, and as someone who refused to compromise quality for quantity in research for the sake of publishing exposure.

Lastly, I’d like to be remembered as a woman who gave opportunities to young people and improved conditions in less privileged areas of the world.

Learn more about our Department of Chemistry.